After the previous winter of freezing as clients Spey cast their flies into the back of my head, the idea of reversing the seasons by guiding fly fishermen and fishing during the Chilean summer was quite appealing. Unfortunately, I am old enough that when I started looking for South American employment the incursion of North Americans into the Andes in search of trout was still in its “Wild West” days. There was a myth being perpetuated by whispered rumors of huge trout that rarely saw a fly. In the burgeoning days of the Internet, there were unsubstantiated articles about open expanses of cheap land that could hold a lodge built specifically for trout hungry Anglos. The rich, fat ones that had wads of cash spilling from their pockets in particular.

These stories cast a rosy hue on everything that I had learned about guiding in Chile. Even the warnings I had gotten from one of my best friends who had spent the summer trying to get paid for his work at a lodge near Coyhaique the previous winter couldn’t weaken my resolve. I was going to guide on the Andean crystalline waters while condors soared overhead no matter what. That is why I bit harder than a summer steelhead when I got a response from one of the 7 or 8 emails that I had sent out to various lodges located in the Southern Hemisphere.

Please don’t think that I was totally naïve. The shining answers to the questions I sent via AOL about bookings, wages, living quarters and the fly fishing were answered with enough ambiguity that I was a little leery. What sold me was the phone call from the owner. Steiner came across as an earnest, honest man who had built a bastion in the wilderness rife with monster trout and clients to catch them. Signing the contract as it came off of the fax machine without reading it because of what I had been told on the phone was probably the single most idiotic thing I have ever done.

That is how I ended up in the middle of nowhere, a sulking fixture sitting on a high bank of the little river named El Malito with my Sage and a six-pack. Apparently the locals, from way back when, didn’t feel that cursing the little stream with such a name, which translated means “Little Evil”, was enough.

My three fellow guides and myself were garrisoned in a small farmhouse just outside of a small village that also bore this name. Of course, the reason for such a malevolent sounding name had died with the town’s mayor’s great-great-great-great grandfather in whose house we were living. Short memories and disinterest in all things asked by “The Gringos”, which we had been dubbed, seemed to plague the inhabitants of our short-term home. This became apparent when I asked how the town and river came by their names and I got a blank stare followed by; “No es importante. ¿Tiene un camello?”

It would soon become apparent that there was a strange indigenous linguistic pattern that was manifested at the end of almost every sentence spoken by our hosts; “Do you have a Camel cigarette.”

A dull, hopelessness had been seeping into my psyche during the entire 14-hour journey with Steiner from Puerto Montt. It had become clear within minutes of meeting him that he knew less about fly fishing than he did running a lodge. I still waffle on which subject he knew less about even 20 years later. His face was contorted into scowl most of the time, only cracking into a microscopic smile when he was talking about himself. Thinking back he had that smile on his face a lot.

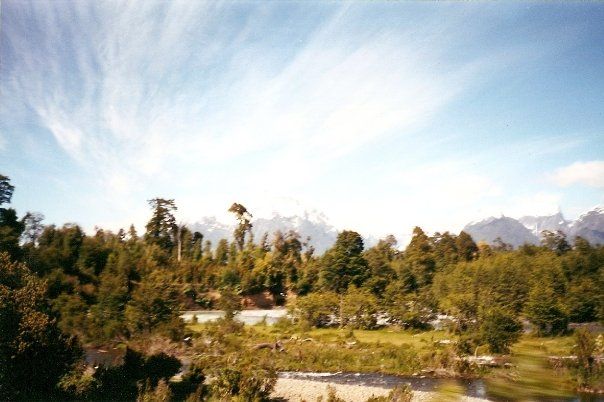

The drive was beautiful. Our little two-vehicle caravan wove through the glacier-laden mountains and cypress forests that cascaded down the slopes below the icy valleys until they were stopped by a river or a lake. We drove past countless rivers and lakes. The first half of the trip one of us would ask Steiner if we guided on the lake or river we were passing. He would grimace and say; “They don’t fish very well, I don’t take my guests where there are no fish.” This was the only thing that he said for at least 3 hours, so we quit asking. Ironically, we passed three lodges that were on the water that he said didn’t fish very well. My foreboding grew with every kilometer.

With no warning, we turned off of Highway 7’s loose gravel and tore through a pasture that had ten times the sheep in it than it should have had for the amount of grass that was growing. A little yellow house jumped into view as Steiner hit the brakes throwing us forward hard enough that our load of food in the back of the truck shifted. He immediately blamed me, a common theme for the next four months. As he got out of the little Mazda four-door truck he cussed me, told us this was where we were staying and slammed the door without breathing or smiling. Then I saw it.

There was hope flowing behind the old house. A small, gloriously crystal clear little stream that had a river’s name was running less than 70 feet from what was soon to be my room’s window. I was in love with Rio Malito from the first time I saw it. My gaze never left the pool that ran silently below a steep bank a little over a rod length high as we unloaded. “I will see you in a couple of days;” Steiner gushed with childlike glee as he left us with our rods, gear bags and packs in a big pile in front of us and the old couple who would be our hosts. I knew that my time in Region X, known as the Lakes Region, was going to be an “experience” from that point forward.

Fishing The First Night

Unpacking my bag that had a season’s worth of fishing gear including waders and rods didn’t take too long. Traveling light was a specialty and I was situated before the others. I was sitting on the front porch swatting the random mosquito that dared attempt my flesh while I strung up my 5wt rod when the other guys appeared. As I offered each of them a beer a look of relief came across all three of the younger men’s faces. They had carried a shell-shocked expression on their faces from the first moment they had met our new boss. Beer was needed.

Chaitén hadn’t had much that I had needed but I did buy as much beer that I could without Steiner noticing. The four cases of Cristal in cans were 50% cheaper than what the lodge would charge us. I guessed correctly that Steiner would have taken one of my cases of beer for hauling it to Malito if he would have seen it. He took one of the four six –packs that Bill had bought when he left that evening. Bill was somewhat superstitious I would find out later. He said; “That’s a bad omen,” as Steiner drove off with a quarter of his beer supply.

Steiner liked the younger guys better than me from the beginning. I was 34 and had been guiding for a long time. My counterparts were barely of legal drinking age, in the U.S. that is. To my shock, Bill volunteered that our industrious leader had told them the night before we left from Puerto Montt that there were only 12 guests booked for the entire season!

On cue, we all took long swigs of our beer simultaneously when Bill finished telling me this good news. We had all been assured that the lodge was full for the season. We were now stuck in a foreign country with little to no work. Yeah, we were salaried, but clients meant tips that were often more than our salaries. This news was a little worse than I expected, but 30 seconds after meeting Steiner I knew this winter was going to be a mess.

Chugging the last of my beer down with a slurp for emphasis, I stood up as I grabbed my rod and a couple of cans of beer. Looking at the confused and sullen faces was depressing me. Stepping between the guys and off the porch, I headed towards the little river that I could have reach easily with a cast from our front yard if we would have had one. Without looking back I said; “I guess it is time to go catch my first fish in Chile.”

There were three sets of eyes on me as I reached the bank above first pool just below the house. Plopping down on the sheep shorn pasture grass was like sitting on a golf green. This would be the first night of a ritual that would take place many evenings for the next 4 months. Immediately a beer was opened and a cigarette came out and was lit to ward off the cloud of bugs that appeared. Cigarettes aren’t good for you, but Chilean cigarettes must give mosquitos instant cancer because I haven’t found a better insect repellent to this day. Getting everything in order, I started watching the pool to see what was happening, ignoring my audience. Soon the weight of the fellas’ eyes watching me was gone, quickly followed by the sound the door closing. At last, I was alone for the first time in days. It was time to watch for a fish or two and try to forget the big mess that I had gotten myself into for the next few hours before the sun went down.

A nose appeared at the edge of the current. There was no ripple, no ring, no disturbance of any kind as the fish slurped down a little mayfly. The little pool was about the length of two small cars and just a little wider than one. Where the fish was feeding was maybe 10 feet from me. It wasn’t big, but it made me feel better while I drank my beer and smoked, all the while watching for more fish noses and bugs. Shade from the mountains had fallen over the little river’s valley just after I sat down. A breathy breeze accompanied the mountain’s shadow making the willows tremble that lined the banks of the little river. For a moment I felt like I was at home. Then I heard a condor. Looking off into the distance I saw my first condor soaring so high that it was still in the sunlight. “You’re in Chile;” I said to myself.

The beer can seemed to empty itself. Time to catch the fish that had become several. Random little yellow mayflies soloing with their new wings over the water were becoming more numerous, a full-blown hatch. The fish were patiently waiting for the little bugs to drift over their heads in a current that had been flowing cold and pure for thousands of years. Watching the Brown trout feed mesmerized me to the point that I opened another beer without thinking about it. As I instinctually put the green can to my lips a larger head appeared as it ate one of the insects. The appearance of this bigger trout snapped me out of my hypnosis. The fish had eaten the little fly and disappeared into the colored stones that littered the river bottom. It was time to fish.

Sliding down the short steep bank on my rear so I wouldn’t put the trout down seemed like the right approach. Halfway down the short 9-foot bank I knocked a small red rock loose that “clacked” loudly down the slope until it made a “sploosh” sound when it went into the water. Groaning, I figured I was done there for the evening. Looking upstream there were sipping fish everywhere, they were totally oblivious to me and my rock.

So I stood up from where I was and got ready to cast my PMD up to the big guy I had just seen rise. At that moment I told myself that none of these trout had ever been cast to, let alone cast to by a “Gringo”.

A Long Way From Home

For that moment I had forgotten that I was several thousand miles from Oregon. I could have been anywhere there are trout that rise to dry flies. My universe had been reduced to a stream and a feeding fish. There was nothing more important than the brown trout a few yards away, not a worry or longing seeped into my thoughts. Slowly the line fell from my little Ross reel into the water at my feet as I pulled it instinctually from the spool, the motion of my hand unnoticed by my brain. My gaze never left the spot where the trout was sucking bugs from the surface of the stream as I made my first false cast over the heavier current to the right of the eating fish. After the little practice cast to get the distance right, I managed to get the PMD to land right where I wanted it to fall. Executing what I was sure was the perfect cast to the soon to be hooked fish put my fish hypnosis on overdrive.

The ghost of Hemingway’s young soul, Nick Adams, could have appeared out of the willows across the stream from me without me noticing, even if he was trying to poach my water with a worm. Cautiously I stripped the fly line in as the fly floated back towards me as it went within a whisker’s length of my target. The fish wouldn’t be able to resist my fly, I felt it in my bones. There was a primordial anticipation tensing my hands. Time ceased as the fly came to the exact spot where the fish lurked. Without thinking I set the hook, more on intuition than actually seeing the fish suck my fly under the surface. It was predestined that my fly was going to get that large gold blur into my hand the second I saw it eat that first mayfly, two beers earlier.

As my line went tight a fish rose within inches of where my fly had just disappeared. It was too late to slow down the mildly vicious, somewhat overly powerful hook set that I had initiated. The ripple from the rise of the trout that I had wanted to hook was rolling over the spot where I had just hooked the super dink brown which was now airborne. “It figured with the way the last few days have gone;” I thought as the little fish landed with a subtle “Ploop “ in the shallow water that was surrounding my submerged ankles. Then there was nothing but the sound of the water rushing through the rocks into my pool. The little fish had released itself from the fly after its short flight. It was clear that it was time for another Cristal.

My Best Friend

Listening to the river as the shadows became darkness, a soft peacefulness draped itself over my little river that I hadn’t felt for a long time. The fish continued eating the pale yellow mayflies in the blue light, this was the friendliest feeling I’d had since I left the United States. I headed back to my little room in the old farmhouse when all that I could see was the reflection of the Southern Cross in my pool, the dim light from my new window glinting off of the silver top of my one remaining beer.

A day felt like a week and a week like a year in Malito. The lodge sat empty most of the season on the bluff above the big river a few miles from our house. We seldom went to the worn and warped 12 room building. Steiner ruled from the beautifully crafted table in the dining room that was held in place by the weight of several half-empty whiskey bottles. He would hold guide meetings with us at the table where he would just stare out the picture windows that overlooked the river, never making eye contact with any of us. As he looked wistfully towards the water with a glass of liquor of some sort, he wasn’t picky, he would usually tell us that another group of guests had canceled. After these proclamations of failure, he would dourly give us some chores to do around the lodge because; “I can’t pay you for nothing.” This usually meant that the gathering was over. Then he would refill his glass from a random bottle from his collection and walk into the kitchen. There we would hear him terrorize the poor Chilean kitchen staff that he had shanghaied from Santiago with grander promises then he had made to us, if that was possible. The only constant for me was my evenings alone on the Malito with my trout.

The weather in southern Chile is somewhat fickle, to say the least. It was no surprise to me that when the lodge actually got some clients it started raining buckets for two weeks solid. We were trapped in guide purgatory. Steiner’s would careen through the small ponds that littered the muddy road to our house every morning to take us to the lodge. Wind and rain would pelt the truck the whole way to the lodge making it hard for us to hear him as he made his daily excuses of having to go to town for something. Often he wouldn’t even get out of the truck. He would just leave us standing in the driveway in our Simms rain jackets in the rain, a somber quartet of damp, melancholy guides watching his taillights fading into the mist.

It was during this time that Steiner disappeared for three days. The guests were left alone for the same dreary three days in the cavernous great room of the lodge that faced the big river. The only time I saw most of them smile during their stay was during his absence. On the second evening, we walked the road to the lodge out of boredom. When we arrived, the guests and the lodge staff were having a joyous dinner together at the big table. Laughter bounced through the forest of wine bottles that had sprung from the table and this was the only time that I ever remember anyone having fun in that building.

After a glass of wine or two I thought about my little stream. Excusing myself from the festive crowd, I walked back to the little river with my hood pulled low around my face. The pull of the little Malito was too strong, drawing me from a happiness and warmth that I hadn’t seen for weeks. Reality tends to thrust itself into moments joy. About halfway through my walk back to the river, Steiner and his truck zoomed by me as if he knew that something fun was happening in the lodge and he had to go stomp it out. Later that evening I would hear that he successfully repelled the few moments of joy that the guests had experienced since their wet arrival. His efforts were so fruitful that half of our fishermen left the next day, only three days into their stay.

Splashing my way down the muddy road towards the little village of Malito that evening I thought about Chile. I had been there almost three months and had only guided a total of 16 days during that time. My finances were going to be in deficit after this little foray. I had met and worked for the modern version of Kurtz from The Heart of Darkness. I had to guide on a river that had come up 16 feet in one night with a fisherman who asked me why they weren’t catching anything as a dead cow floated by the boat. Streamers the size of small fish continually were slammed into my head by anglers fighting to cast against the constant 30 MPH winds. I added to the list with every step I took towards the village.

All of these negatives were still overshadowed by the love that I had found for the rugged, rural landscape that held so many rivers and lakes with large hungry trout. I had only gotten a small taste of the famous waters like the Futalafu and Lago Yelcho. They surrendered some of my best memories that I have as a guide. From my guests catching monster Brook trout on #2 Dragon Fly dries in Lago Yelcho to netting a client’s a 38 inch Brown trout in the front of my drift boat on the Rio Palena that I had spotted as I rowed to my 10 miles on a horse that I had to ride to some remote lakes because I was the only one who had been on a horse, the memories are still vivid to this day. But the most vivid ones are of my times on the Malito by myself killing the monotony and frustrations of the empty days. The miles of the little stream that was called a river had become my best friend in Chile.

The rain let up just as I sat down with my beer and my rod above the pool that evening. A warm breeze barely rustled the willow leaves that were dangling over the

water across the creek from my lookout spot. Gazing down towards the spot where the big Brown was feeding on my first night fishing in Chile three long months ago, I took a drink from the can of Cristal. The bubbles danced over my tongue as I swallowed. There was nothing more, just myself and my river in the universe at that second. There was no Steiner, no worries about money or unhappy guests invading my thoughts as I sat alone.

Emerging slowly, the golden head of the large trout I had first seen some months ago appeared as it gently took a small bug into its mouth. He was back. I hadn’t seen him since that first evening even though I had spent hours contemplating his return as I watched the pool from above. Now he was within two-rod lengths of me, unaware of my presence. Fighting the anticipation, I waited for his feeding to become more steady.

There were no other fish rising. He was alone in the little run, he had made it his. The water was carrying more and more insects over the top of him. He began to eat at a frenzied pace. Bug after bug disappeared into his mouth as the rises became more violent. When the entire length of the dappled fish’s body came out of the water as he grabbed a PMD out of the air I decided it was time. Taking my fly off of the hook keeper on my rod I stepped down the bank and into the exact spot of my previous failure.

A loud grinding of gears echoed over the bank of the river as my fly landed for the third or fourth time just above where my trout was eating. I heard Steiner’s voice barking at the other guys as the pickup doors slammed shut. His voice sounded even more slurred than was normal for this time of night as he drove away still yammering away. The distraction of their return had caused me lose sight of my fly for just a second. That’s when my line went slack and started swimming past me, a slack belly of line hanging from the tip of my rod. Swearing, I started to frantically strip. The line hung hopelessly limp forever it seemed as I struggled to get the hook wedged tight into the lip of fish. Uttering a prayer laced with obscenities as my line came tight, the fish came to the realization that he was in danger.

My rod was instantly doubled in two as it withstood a short, powerful run back to the head of the pool where he had taken the fly. The rod tip bounced, undulating in the dusk as head shake after head shake tested my leader. Momentary hopelessness overcame me, all I could do was to hold on and wait. Turning suddenly in the current, the fish was at my feet looking even larger than it was as the water magnified its red spots into the size of gumdrops. My arm was straight up in the air with the soft 5wt. rod bending under the strain while the fish rested within inches of my toes.

I couldn’t budge the trout. It felt like an anchor was on my line. He was using the current and his girth to resist my efforts to move him the foot to the shore. I could see my fly in its mouth and the slight piece of flesh barely keeping my hook in the fish. Instantly I knew it was time to land the fish or I was going to lose it. Spinning downstream, I gingerly turned the fish with the current, leading it like a dog on a leash. There was no furious outburst, nothing but a docile tail flush that pushed him right onto the little sandy spot where I wanted him. It was over.

My fly came loose the instant the trout was on its side on the sandy spot in the shallow water. He didn’t move. I didn’t move. Standing there for a second it, I looked up at the Southern Cross feeling its presence as it peered down at me through a hole in the graying night. Expressing pure joy in words is the toughest task in the world, but that is what I felt at that moment. I felt electric as I nudged the fish back into the frigid water. He disappeared with two methodically slow sweeps of his tail.

Three weeks later I would catch my last fish on the Malito. None would be like the one on that stormy night that settled long enough to hook that one fish. It has been almost 20 years since I have explored the river’s rocky runs and still pools. Even with time passing and my many fishing stops, I still tell people it is one of my favorite places on earth to fish. The extraordinary solitude of the river’s invisible, healing waters and golden Browns fades into heavier and heavier vaporous shadows with each passing day. All that truly remains, are the essences of the Rio Malito, beer, and Brown trout. That is good enough.